The truth about stories is, that's all we are.

~Thomas King

~ The Importance of Reading Aloud

I loved that this course brought back so many memories of my own childhood - one filled with parental love and the wonder of reading. I remember the books my parents bought and the feeling of snuggling close to my Mom as she read me stories. It also brought back memories of similar moments with my own children. In these moments the child feels loved and the bond between caregiver and child is strengthened.

What Next in the Read Aloud Battle? by Mem Fox reinforced for me the power of reading aloud to spark joy in stories and text. Fox writes, "Listening to an adult read aloud cultivates the essential enchanting engagement with books, stories, rhymes, and songs that every child needs to experience before the formal teaching of reading can begin" (Fox). This article made me think about the way children respond when they are read to. They delight in and respond to the fun word sounds, to the rhythm of language, and to the intonation and expression of the reader.

Reading Aloud to Young Children Has Benefits for Behavior and Attention by Perry Klass references a study by Dr. Mendelson which links reading to young children to positive behavior and better attention spans in the years to come. According to Mendelson, reading aloud is a form of play which results in social-emotional development (Klass, 2018). While I have always known that reading aloud is a form of play and that it helps with social-emotional development, it was surprising to see the lasting effects of reading aloud on children's behavior and attention. This lead me to think about ways in which we, as a community, could provide better support and education for new parents so that all children have the best possible start with reading and the cultivation of self-regulation and focus.

~ Language and Children's Literature

This module has me thinking about the role of reading in language development, which in turn makes me wonder how language development is linked to other types of intellectual development. This module, combined with the one before it, encourages me to continue to read aloud to students and to seek out more ways for students to interact with stories and language in a social context.

The Language and Learning Theories of Halliday and Vygotsky and their Contributions to Educational Practice by Zhao Xia gave me the language to talk about how learning occurs through reading to young children. This article explains that both theorists and their schools of thought "hold that language learning takes place in a social context and each considers language to be a product of human construction." Children learn language in the social context of interaction with their

caregivers.

The videos in the introductory module reminded me of a video of my daughter's favorite first book, Mr Brown Can Moo, Can You? The book is thick, sturdy, and glossy, making it strand up to handling by drooling children who might like to put it in their mouths. This last month I was able to think about why this book is a favorite - it's interactive and fun to read. It's representative of many Dr. Seuss books with its eccentric character(s), imaginative drawings, and fun words and phrases with strong rhyme and meter. The story makes use of animal (and other) sounds and uses simple wording with strong rhythm and rhyme.

It was wonderful to re-watch this video of my

husband and daughter reading Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? I hadn't thought about or looked at the video in more than ten years. It felt as though I was swept back to another time and place bringing tears to my yeas as I remembered those shared years. My daughter also enjoyed viewing herself at this age. I hope it will have a lasting impression on her and encourage her to read to her own children if she ever becomes a mom. In the video she can be seen mixing in a few Spanish words with English ones. The Zhao Xia article I mentioned earlier states that Vytotsky's theory of language development "promotes learning contexts in which students play an active role in learning"(Xia). The book Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? is one which lends itself to interactive play.

I loved that this course brought back so many memories of my own childhood - one filled with parental love and the wonder of reading. I remember the books my parents bought and the feeling of snuggling close to my Mom as she read me stories. It also brought back memories of similar moments with my own children. In these moments the child feels loved and the bond between caregiver and child is strengthened.

What Next in the Read Aloud Battle? by Mem Fox reinforced for me the power of reading aloud to spark joy in stories and text. Fox writes, "Listening to an adult read aloud cultivates the essential enchanting engagement with books, stories, rhymes, and songs that every child needs to experience before the formal teaching of reading can begin" (Fox). This article made me think about the way children respond when they are read to. They delight in and respond to the fun word sounds, to the rhythm of language, and to the intonation and expression of the reader.

Reading Aloud to Young Children Has Benefits for Behavior and Attention by Perry Klass references a study by Dr. Mendelson which links reading to young children to positive behavior and better attention spans in the years to come. According to Mendelson, reading aloud is a form of play which results in social-emotional development (Klass, 2018). While I have always known that reading aloud is a form of play and that it helps with social-emotional development, it was surprising to see the lasting effects of reading aloud on children's behavior and attention. This lead me to think about ways in which we, as a community, could provide better support and education for new parents so that all children have the best possible start with reading and the cultivation of self-regulation and focus.

~ Language and Children's Literature

This module has me thinking about the role of reading in language development, which in turn makes me wonder how language development is linked to other types of intellectual development. This module, combined with the one before it, encourages me to continue to read aloud to students and to seek out more ways for students to interact with stories and language in a social context.

The Language and Learning Theories of Halliday and Vygotsky and their Contributions to Educational Practice by Zhao Xia gave me the language to talk about how learning occurs through reading to young children. This article explains that both theorists and their schools of thought "hold that language learning takes place in a social context and each considers language to be a product of human construction." Children learn language in the social context of interaction with their

caregivers.

The videos in the introductory module reminded me of a video of my daughter's favorite first book, Mr Brown Can Moo, Can You? The book is thick, sturdy, and glossy, making it strand up to handling by drooling children who might like to put it in their mouths. This last month I was able to think about why this book is a favorite - it's interactive and fun to read. It's representative of many Dr. Seuss books with its eccentric character(s), imaginative drawings, and fun words and phrases with strong rhyme and meter. The story makes use of animal (and other) sounds and uses simple wording with strong rhythm and rhyme.

It was wonderful to re-watch this video of my

husband and daughter reading Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? I hadn't thought about or looked at the video in more than ten years. It felt as though I was swept back to another time and place bringing tears to my yeas as I remembered those shared years. My daughter also enjoyed viewing herself at this age. I hope it will have a lasting impression on her and encourage her to read to her own children if she ever becomes a mom. In the video she can be seen mixing in a few Spanish words with English ones. The Zhao Xia article I mentioned earlier states that Vytotsky's theory of language development "promotes learning contexts in which students play an active role in learning"(Xia). The book Mr. Brown Can Moo! Can You? is one which lends itself to interactive play.

~ Views of Childhood

In this module I reflected on the contradictory idea that books both shape our perceptions of childhood and are shaped by society's perception of childhood. I am fascinated by the idea that stories are the result of books written by an adult for the child and that the child in the book is the image of the type of child the author has in mind - a combination of the views they have inherited from their society and of their own remembered experiences of childhood. It is important to understand these concepts in order to understand the degree to which our own society and past experiences as a child have shaped our book preferences and the books we share with children.

The video, Maurice Sendac on Being a Kid helped me to think about the degree to which our childhood experiences shape our view of childhood. Maurice's childhood was less than idyllic, as many childhoods are. He faced difficulties but was able to persevere through them. He was exposed to and appreciated European stories about children in terrifying situations. These experiences shaped his perception that childhood is a tough time, but children are capable of solving complex problems and capable of surviving adverse circumstances. These views, in turn, have shaped his writing, which is never condescending and does not downplay the struggles children face. Sendak says, "I still think the same way I did as a kid. I still worry. I'm still frightened...Nothing changes." I clearly when I was a child I disliked when adults talked down to me. I remember when I was six years of age reflecting on the fact that I felt myself a fully capable intelligent human being with complex thoughts, but that most adults did not realize how capable and intelligent I actually was. Sendak's understanding that much of what we think and feel does not change between childhood and adulthood gives his work a depth and complexity that some children's stories lack.

Historian's Discovery of Childhood by W. Frihoff was a dense, but fascinating read exploring the way societies have viewed childhood over time. I was interested to learn that the entire concept of childhood is quite recent to Western thought. I was especially intrigued by Frigjoff's suggestion that children and YA literature is always written by an adult to an idealized child. When writing children's books adults have the child they once were in their minds, therefore creating texts about imagined children of a prior time and place. An extension of this idea is echoed in the articles by Hill, Rata, and Short. These later articles postulate that this situation of the adult writing for an imagined child creates an imbalance of power between a text and its young reader. Rata writes "T]hese books must represent the adults' values, morals, knowledge, ideas that are manipulating the child reader" (Rata, 2014). I will discuss Rata's article later in this curation, but I wanted to point out how she has gone further with Frihoff's initial premise in suggesting children's texts may have tremendous ideological influence over the reader.

Lucy Maud Montgomery's Anne of Green Gables is included in my curation because it is an example, for me, of a story from my childhood which had an influence on my values and interests. It helped to shape my love of nature, a belief in the independence of women, a value for creativity and individual expression, a sense of community mindedness, and an interest in reading, writing, and teaching. Perhaps we are more susceptible to the texts of our youth because it is a time of rapid intellectual, social, emotional and physical development. Our identities are more malleable. Irina Rata writes, "Children's books have the potential to be the most influential books in someone's life, being the first books that a person reads; having the power to form the reader's personality, character, value system, and even the reader's taste" (Rata, 2014).

~ Context and Literary Canon

This module in combination with the last one helped me to see how my society and my past experiences as a child have influenced my personal canon. I recognize that my book selections for young children are a result of my own time period and culture. They have shaped my perceptions of childhood as a time for imaginative play, learning, and for finding a place in the world with others. These perceptions have their root in an idea of the child has both "socially constructed" and as a "psychologically and intellectually developing human" (Delvechhio, 2019). Also, the reflection task I completed - to create a canon for the first ten years of a child's life - also lead me to see the degree to which my book selections are a product of my own white privilege as they do not represent my racial or ethnic diversity. A next step for me will be to keep this awareness going forward so that my selections become more inclusive of a diverse range of cultures, genders, abilities, and socio-economic perspectives.

Literacy Leadership Brief. Expanding the Canon: How Diverse Literature Can Transform Literacy Learning by The International Literacy Association (my own research) advocates for the redefining of what makes a classic as "a title that succeeds to an unusual degree in expressing the shared experiences of humanity through an artistically significant creation" and suggests a "more expansive approach to literature selection that can redesign and ultimately redefine the narratives that define the classroom library" (The International Literacy Association, 2018). I agree with the idea of finding diverse pieces of literature that still exemplify great writing. I also appreciated the article's suggestion that if students are regularly exposed to diverse texts they will "internalize issues of diversity as part of the human condition, not as adjunct material for certain holidays or topics" (International Literary Association, 2018).

~ Poetics: What Makes Some Literature Literary

This is one of my favorite modules to read and think about because in some ways it has been a part of my life's work. From the time I was a teenager I have been thinking about great books and great passages of text. When I was in grade nine I began keeping a journal with passages that I admired or that inspired me. I was inspired by the idea that children's literature is often great writing.

Module 5: Poetics: What makes Some Literature Literary by UBC Professor Jennifer Delvecchio defines writing which is literary as that which provides new perspective, contains multiple layers of meaning with themes, and uses language uniquely. These module notes were a good starting point which laid a foundation for further reflection and reading about "literary" texts.

Children's Literature - A Cinderella Story by Irene Rata points out that much children and YA literature, "may surprise the reader with unexpected depth and intricate narrative, beautiful language and deep subtle human motives, literary innovations, and difficult themes treated with grace" (Rata, 20). The article argues that definitions of children's and YA literature are inconsistent and that it has been largely dismissed or ignored by literary critics. The article points to a number of qualities that make it unique and deserving of literary study. I particularly appreciated Rata's point that "as a genre [children's literature] mirror's the literature in general with all its genres and forms" and that it is "an interesting object of study, where one may rediscover the pleasure of reading, and uncover unknown things" (Rata, 2014).

The Book Thief by

Markus Zusak, is included in this curation because it is a fine

example of a story which fits Rata's description of great YA

writing. The plot is far from simple, containing a non-linear

narrative with multiple plots and sub-plots, multiple secondary characters, and

multiple points of view. It also employs anachronies - flashbacks

and flash-forwards, prolepsis - the anticipation of possible objections in

rhetorical speech, and analepsis - a past event narrate later.

These are all mentioned in Rate's article as frequent features of adult

literature, but also a surprisingly large amount of children's and YA

literature. I also loved this novel because, above all else, it was a

story about the power of words.

The Book Thief by

Markus Zusak, is included in this curation because it is a fine

example of a story which fits Rata's description of great YA

writing. The plot is far from simple, containing a non-linear

narrative with multiple plots and sub-plots, multiple secondary characters, and

multiple points of view. It also employs anachronies - flashbacks

and flash-forwards, prolepsis - the anticipation of possible objections in

rhetorical speech, and analepsis - a past event narrate later.

These are all mentioned in Rate's article as frequent features of adult

literature, but also a surprisingly large amount of children's and YA

literature. I also loved this novel because, above all else, it was a

story about the power of words.

Empathy: Narrative Empathy and Children's Literature by K. Mallan is an article which is sticking with me because it argues against what I have, for years, believed to be true. The article refutes the nation that reading has an impact on the ability of the reader to "become more empathetic, tolerant, and better people" (Mallan, 2013). This article made me uncomfortable, but I appreciated its nuanced and challenging discussion of the way empathy works in stories and the notion that "fiction that engages a reader with the emotional plight of a character does not necessarily translate into actions in the real world towards people who are similarly suffering, marginalized or victimized" (Mallan, 2014). There was a lot to unpack in this article. Mallan also points to oversimplification in reducing complex situations to binaries such as "victim" and "savior" and criticizes "one off acts of empathy while failing to address institutional, corporate, systemic abuses of power that are much more toxic, powerful, and oppressive than anything an individual can individually commit or, conversely, repair" (Mallan, 2014). If I am to accept what this article is saying then I agree with the article's conclusion that urgent work of pedagogy and children's literature studies in needed to realize the potential [critics such as Rorty and Nussbaum see] of literature for reimagining a more empathic, moral, and compassionate world" (Mallan, 2014).

The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time by UK writer Mark Haddon, is in

my curation because it presents round characters, such as the autistic

protagonist and his mother. Instead of presenting an image of maternal

gentleness and protection Christopher's mother is depicted as a person

with complex and competing motivations and emotions. The complexity of the

motherly depiction defies stereotypes. The text neither idealizes her or

turns her into a villain. Using Rudine Sims Bishop's metaphor

(which I will discuss later), the text is one which offers a mirror to readers

who process the world differently (such as people with autism) and to those who

have experienced family dysfunction. The text is a sliding glass

door to other readers, "allowing them to walk through in imagination to

become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author"

(Bishop, 2018; cited in Delvecchio, 2019). The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time may help readers to do what Christopher cannot

do - that is, infer the feelings of others.

The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time by UK writer Mark Haddon, is in

my curation because it presents round characters, such as the autistic

protagonist and his mother. Instead of presenting an image of maternal

gentleness and protection Christopher's mother is depicted as a person

with complex and competing motivations and emotions. The complexity of the

motherly depiction defies stereotypes. The text neither idealizes her or

turns her into a villain. Using Rudine Sims Bishop's metaphor

(which I will discuss later), the text is one which offers a mirror to readers

who process the world differently (such as people with autism) and to those who

have experienced family dysfunction. The text is a sliding glass

door to other readers, "allowing them to walk through in imagination to

become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author"

(Bishop, 2018; cited in Delvecchio, 2019). The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time may help readers to do what Christopher cannot

do - that is, infer the feelings of others.

~ Sequential Visual Narrative Forms

This module was a study on the role of images in not only picture books, but also comic strips and graphic novels. As someone who loves art, I have a deep appreciation for images, but I have had only a little experience reading comics and even less experience with graphic novels. For that reason the last few weeks have been a delightful immersion into this form and have opened my eyes to their value for instruction and as literature. Images, like text, can do the work of telling a story using all the same genres of other novels and with all of the possibilities of being of literary merit. Plot, character, events, and actions may be conveyed through the language of images rather than words. I am discovering the potential of the medium to tell a story, convey complex ideas across subject areas, use with students as a type of multi-modal response, and move me to a sense of wonder.

A Meditation on the Good Old Picture Book by Janine Forbes-Rolfe points out the literary qualities of a picture book. The article explains, "The humble picture book may seem deceptively simple in form, but the best books always manage to belie this apparent simplicity, creating rich experiences that potently shape how young learner makes sense of the universe. I appreciated this article's perspective that a picture book can be literary and that the best picture books are foundational to how young minds begin the early process of constructing meaning and defining their surrounding" (Forbes-Rolfe, 2015).

Are You My Mother by P.D. Eastman is the type of foundational book Forbes-Rolfe says a picture

book can be. Written in 1960, this picture book story is about a baby bird in

search of his mother. He tumbles to the ground after hatching while his

mother is away from the nest. What ensues is an endearingly sweet and

funny quest to find his mother. The effectiveness of this story

rests not only on the humorous illustrations and dialog - the repeating

question "Are you my mother?" and "You're not my mother,"

but at the metaphorical level of the reader seeing his or her own search for

identity and belonging in the baby bird's search. The story

meets definitions of what is literary as presented by Delvecchio in Module

5 in that it provides new perspective, contains multiple layers of meaning

with themes, and uses language uniquely (Delvecchio,2019).

The

illustrations in Are You My Mother are essential to the story,

as without them the reader would not understand who or what the little bird is

talking to and would not understand how the baby bird is reunited with its

mother. These illustrations are rendered with a limited color palette

of muted brown, yellow and red. The images focus solely on the baby

bird and his search, without any other details. Despite it's brevity, simple images,

and simple sentence structures, it manages to touch on the universal theme of

belonging.

Are You My Mother by P.D. Eastman is the type of foundational book Forbes-Rolfe says a picture

book can be. Written in 1960, this picture book story is about a baby bird in

search of his mother. He tumbles to the ground after hatching while his

mother is away from the nest. What ensues is an endearingly sweet and

funny quest to find his mother. The effectiveness of this story

rests not only on the humorous illustrations and dialog - the repeating

question "Are you my mother?" and "You're not my mother,"

but at the metaphorical level of the reader seeing his or her own search for

identity and belonging in the baby bird's search. The story

meets definitions of what is literary as presented by Delvecchio in Module

5 in that it provides new perspective, contains multiple layers of meaning

with themes, and uses language uniquely (Delvecchio,2019).

The

illustrations in Are You My Mother are essential to the story,

as without them the reader would not understand who or what the little bird is

talking to and would not understand how the baby bird is reunited with its

mother. These illustrations are rendered with a limited color palette

of muted brown, yellow and red. The images focus solely on the baby

bird and his search, without any other details. Despite it's brevity, simple images,

and simple sentence structures, it manages to touch on the universal theme of

belonging.

The Day the Babies Crawled Away, by

Peggy Rathmann also meets definitions of writing which is

literary and has become important in my thoughts about children's

literature over the past several weeks as it was the starting point for my

curation in Assignment 2. Similar to Are You My Mother, this

story also contains images which help to narrate the story. The pictures

are fascinating and fun, as the reader searches through each of the detailed

images carefully to locate the numerous run-away babies (up in a tree, in a bat

cave...). Beyond it's fascinating sharp images and repetition of

sound using alliteration and rhyme, according to UBC Professor Jennifer Delvecchio the story's unrealistic but fun premise

leads to "imaginings beyond the book itself" and to multiple meanings

based on the prior "experiences and exposures" of the reader.

For Delvecchio these

past exposures include "classical sci-fi works where children of a town

are corralled or brainwashed, 'alien-like' [and] take over."

Delvecchio explains that "past culture and media are integrated into

[her] experiences with this book, not to mention the realities around childhood

safety and precautions" (Delvecchio, 2019). For me, part of the delight of the story comes from the somewhat

subversive idea of children escaping from adult supervision into dark places

and the boy in the firefighter's helmet being rewarded for this adventure

rather than punished.

The Day the Babies Crawled Away, by

Peggy Rathmann also meets definitions of writing which is

literary and has become important in my thoughts about children's

literature over the past several weeks as it was the starting point for my

curation in Assignment 2. Similar to Are You My Mother, this

story also contains images which help to narrate the story. The pictures

are fascinating and fun, as the reader searches through each of the detailed

images carefully to locate the numerous run-away babies (up in a tree, in a bat

cave...). Beyond it's fascinating sharp images and repetition of

sound using alliteration and rhyme, according to UBC Professor Jennifer Delvecchio the story's unrealistic but fun premise

leads to "imaginings beyond the book itself" and to multiple meanings

based on the prior "experiences and exposures" of the reader.

For Delvecchio these

past exposures include "classical sci-fi works where children of a town

are corralled or brainwashed, 'alien-like' [and] take over."

Delvecchio explains that "past culture and media are integrated into

[her] experiences with this book, not to mention the realities around childhood

safety and precautions" (Delvecchio, 2019). For me, part of the delight of the story comes from the somewhat

subversive idea of children escaping from adult supervision into dark places

and the boy in the firefighter's helmet being rewarded for this adventure

rather than punished.

What's Trending in Children's Literature and Why it Matters by Kathy Short was another article with a lot to reflect on. She outlines a number of developments in children's literature, but my interest was primarily in her thoughts on sequential narratives and on the theme of diversity. She notes the current popularity of graphic novels and describes our current time as a "visual culture [...], one in which images, as distinguished from text, are central to how meaning is created in the world" (Short, 2018). Short writes, "Like picture-books, visual images in graphic novels are essential to the telling of the story" and she points out that "[g]raphic novels now cut across genres and age levels to include high-interest series books as well as memoir, historical fiction, informational books, and contemporary fiction" (Short, 2018). In writing about the need for diversity in books Short notes an over-representation of white middle-class protagonists from non-urban areas and writes, "Children who are missing and underrepresented may either take on deficit societal notions of their culture or reject literacy as relevant for their lives, [while] children who constantly see themselves in books....are also negatively affected, as they develop perspectives of privilege and superiority based on false impressions of the world" (Short, 2018).

Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson is important to me because it was the first comic strip series to capture my attention. My first encounter with this strip was in my final year of high school, and I was instantly infatuated. It was my cousin who introduced me to the series. I don't remember a teacher ever encouraging comic book reading in class or in the library. Complex and thought provoking, the characters, Calvin and Hobbes, are multi-faceted and elicit reflection from readers on philosophy and such themes as consumerism and educational conformity as well as the universal themes of love and family. The comics work on multiple levels attracting readers of all ages. The images consist of clear, vibrant colors, often depicting movement. These images, as with comic strips in general, are essential to Watterson's narratives; they are needed to advance the story and they are works of art to be admired in and of themselves. Watterson's images are very much a part of the "visual culture" which Short describes: "one in which images, as distinguished from text, are central to how meaning is created in the world" (Short, 2018).

Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson is important to me because it was the first comic strip series to capture my attention. My first encounter with this strip was in my final year of high school, and I was instantly infatuated. It was my cousin who introduced me to the series. I don't remember a teacher ever encouraging comic book reading in class or in the library. Complex and thought provoking, the characters, Calvin and Hobbes, are multi-faceted and elicit reflection from readers on philosophy and such themes as consumerism and educational conformity as well as the universal themes of love and family. The comics work on multiple levels attracting readers of all ages. The images consist of clear, vibrant colors, often depicting movement. These images, as with comic strips in general, are essential to Watterson's narratives; they are needed to advance the story and they are works of art to be admired in and of themselves. Watterson's images are very much a part of the "visual culture" which Short describes: "one in which images, as distinguished from text, are central to how meaning is created in the world" (Short, 2018).

This comic strip helped me to understand that the terms "comics" and "graphic novels" denote the medium and form, not the genre.

The Awkward series by Svetlana Chmakova is significant to me because it also contributed to my awareness of the fact that I had to learn how to properly read a graphic novel. I had to ask my twelve-year- old son what the boxes at the bottom of the page were doing - revealing the character's thoughts or telling the story. I didn't immediately pick up that this was a story being told in first person narration. I've had to work on my own graphic novel reading skills.

Speak: the Graphic Novel by Laurie Halse Anderson is included here because it may do as Garrison and Gavigan suggest - that is, "provide students with the opportunity to think, react, and question" gender narratives. Speak is a contemporary work of fiction, which deals with rape, depression, and high school experience. It explores the question, "What does silence look like? How can it be expressed?" Illustrator, Emily Carrol does a great job of depicting the restrained pain of the protagonist, Melinda Sordino, by balancing the world Melinda sees and experiences in her head with that of the real world. She uses a limited color palette which allows the reader to focus on the mood and tone of what Melinda may be seeing and experiencing. Carroll’s skill as an illustrator shows itself not only in her adaption of the mood and emotion of the story but in the depictions of the small moments and expressions such as when Melinda begins to unravel who her parents are, flaws and all. This text is as funny and heart-breaking as the original novel, published 20 years ago, and the graphics bring additional nuance and depth to the story.

Gene Yang's TED talk, Why Comics Belong in the Classroom, is significant to me because it helped to convince me that graphic novels can be an effective instructional tool. Yang recounts how he used comics to teach students how to do algebra. He explains that students were able to process the sparse text (suitable for readers of varying levels) at their own speed to learn how to solve complex algebraic problems. He also discusses how other teachers are now using graphic novels to deepen student's' understanding of literature, and other concepts. Some teachers are asking students to create their own graphic novels as a multi-modal creative response to other texts.

~ Considerations: Fiction, Novels and the Young Adult Genre

What stood out for me in this module was the idea that while reading stories can accomplish many purposes, it is also a pleasurable activity in and of itself. The purposes for reading are many - to learn literary strategies, to understand the multiple meanings of a text, to understand one's own culture and the cultures of others, to learn about history, to learn about a particular subject, and to understand the many forms, genres, and conventions of a text. At the beginning of each year I have my students do a reflection on the purposes of reading and the reflection becomes a springboard for some good class discussion. After reading this module and the one on multimodal responses I am inclined to try something different than simply a written reflection. I think this question could be explored in a number of creative ways. I appreciated the idea that many people do not like trying to figure out levels of meaning or discussing themes and symbolism (I am not one of these people because I love doing that). I was inspire by Delvecchio's suggestion that students may find more enjoyment through doing creative tasks, such as multi-modal responses, which generate discussion about the way a book works. Finally, I was intrigued by articles which talked about knowing how a text works so that one might be able to resist being manipulated by the ideology inherent in any text.

Young Adult Literature and Scholarship Come of Age by Crag Hill responds to the idea that YA literature is without literary value and provides solid answers to the question "Why study YA literature?" Part of this article echoes and expands upon the notion that children and YA literature is always written by adults and as such contains their ideologies. The article documents literary analysts such as McCallum and Stephens who propose that a readers' total identification with the protagonist leaves readers susceptible to manipulation by the ideologies of the text. When texts contain multiple voices, perspectives, or unreliable narrators the reader is perhaps able to distance himself or herself from the text enough to see its ideologies. The danger of manipulative ideologies is one of many reasons Craig Hill advocates for increased literary analysis of adolescent literature: "When adolescent readers can recognize and articulate the constructs of a text [and] can locate and critique the overt or cover ideology in a novel...they will control the production of meaning and not be controlled by the ideology of the author" (Hill, 2014).

The Outsiders, by S. E. Hinton is included in my curation because of its literary merit, it's use of

poetry (a trend noted in the article above), it's appeal to a wide range of

readers, and for the fact that it is a rare find of a YA story written by a

teen. The story is a first person point of view with a circular

narration - that is, the conclusion ends up being the start of the story. The

novel explores such themes as class conflict, innocence versus experience,

loyalty to family and friends, and the identity of the individual versus that

of the group. Ciara Murphy's article notes that "some of our

favorite characters like poetry" (Murphy, 2015), and this happen to be the

case with Ponyboy Curtis. His favorite poem is one by Robert Frost

- "Nothing Gold Can Stay." It plays a significant role in

the plot of The Outsiders helping to advance one of the novel's

major themes - that of innocence versus experience. It works on a

metaphorical level. Also, The Outsiders is a rare

contrast to the notion that children's literature is always written by an adult

for an idealized child because S.E. Hinton was 16 when she wrote it. It

was written by a teen for teens, and as such it is potentially not the

colonizing force described by Short and others: "The children's books are

produced mainly by adults, because the adult audiences of parents, teachers,

librarians, etc. are the ones to choose the books for children to read and

study. Therefore these books must represent the adults' values, morals,

knowledge, ideas that are manipulating the child" (Short, 2015). Of

course, S.E. Hinton may well have been writing her novel with an adult audience

also in mind, as she too would need to find a publisher and adult purchasers

for her story.

~ Information and Concept Literature Across the Curriculum

Prior to this class I had given very little thought to using stories to teach across the curriculum. I have used non-fiction in my English classroom, but I had not thought of how non-fiction could be presented in a fun way and used in to teach Math or Science. One of our school's social studies teachers uses a variety of novels in her history classes, but this could also happen in any number of curricular areas. Last year I made a concerted effort to purchase a few high-interest non-fiction titles for the library (going against orders from our administration to focus on fiction). I made displays and did book-talks and these books had good circulation. I appreciate this module's many ideas on how to promote information texts in the classroom. Next year I plan to introduce the idea of using informational and concept literature to teach a variety of subjects. I'll have some discussions with other teachers to share some of the books I am now learning about.

On a Beam of Light by Jennifer Berne and illustrated by Cladimir Radunsky is making it onto my list because it is a terrific example of how story, history, and science can be combined. It reminds me that story can be used in any number of subject areas, not just the humanities.

On a Beam of Light by Jennifer Berne and illustrated by Cladimir Radunsky is making it onto my list because it is a terrific example of how story, history, and science can be combined. It reminds me that story can be used in any number of subject areas, not just the humanities.

The Classroom Library: A Place for Nonfiction by T.A. Young, B. Moss, and L. Cornwell provides both good rational for including non-fiction texts in the classroom and for promoting their classroom use. I have made note of several of their ideas to try out next year.

Blood Water Paint, by Joy McCullough is a 2018 book I might choose to teach with or to promote in our library. It's an example of text which is a story about a real person in history, the life of Artemisia Genteleschie, a Baroque Italian painter of the 17th century. This historical fiction is written in free verse from a first person point of view, except for the intermittent flashbacks of the stories told to Artemisia by her mother. Then the writing is in prose and in the voice of Artemisia's mother telling Artemisia the biblical stories of Suzanne and Judith. The stories of these strong women seamlessly weave in and out of Artemisia's own story. The book is definitely literary. There is a lot of innovation of form and many layers of meaning. It connects the reader from past to present as its themes call to mind the #MeToo Movement. This book fits Craig Hill's description of YA literature which is "not just for teenagers anymore" (Hill 2014). This story could be used to explore social issues and to connect various subject areas - English, art, history, psychology and sociology. This book may be an avenue to learning in a variety of areas. The act of story-boarding this book might help students understand the innovative structure of the story and the multiple voices which appear. This book blurs the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction. It also connects to our module on diversity. The story provides a mirror for all women. Even in such countries as the USA and Canada, Artemisia's struggle is the struggle of North American women, and indeed most women; while much has changed there is still too much that hasn't.

Blood Water Paint, by Joy McCullough is a 2018 book I might choose to teach with or to promote in our library. It's an example of text which is a story about a real person in history, the life of Artemisia Genteleschie, a Baroque Italian painter of the 17th century. This historical fiction is written in free verse from a first person point of view, except for the intermittent flashbacks of the stories told to Artemisia by her mother. Then the writing is in prose and in the voice of Artemisia's mother telling Artemisia the biblical stories of Suzanne and Judith. The stories of these strong women seamlessly weave in and out of Artemisia's own story. The book is definitely literary. There is a lot of innovation of form and many layers of meaning. It connects the reader from past to present as its themes call to mind the #MeToo Movement. This book fits Craig Hill's description of YA literature which is "not just for teenagers anymore" (Hill 2014). This story could be used to explore social issues and to connect various subject areas - English, art, history, psychology and sociology. This book may be an avenue to learning in a variety of areas. The act of story-boarding this book might help students understand the innovative structure of the story and the multiple voices which appear. This book blurs the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction. It also connects to our module on diversity. The story provides a mirror for all women. Even in such countries as the USA and Canada, Artemisia's struggle is the struggle of North American women, and indeed most women; while much has changed there is still too much that hasn't.

Non-fiction graphic novels can be every-bit as compelling as its fiction. The graphic memoir, Hey Kiddo by Jarrett Krosoczoka is in my list because it is a powerful story dealing with themes of identity. With images rendered in a a soft limited pallet of oranges and browns, Hey Kiddo is Jarrett's account of growing up with his grandparents and coming to terms with his complex family situation - that is, having a mother who has abandoned him while she deals with her addiction to heroin, and having a father whom he has never met and whose name he doesn't even know. My reaction to this story surprised me. It had me in tears in several places. Despite having grown up in a household with two parents I could feel the pain of Jerrett's confusion and abandonment. Fassbender points out that "the desire to belong is not unique to a certain culture or generation." Krosczoka's images tell a powerful story. Futhermore, Hey Kiddo is also an effort toward increasing diversity in children's and YA literature which Short and others wish to see. It depicts a non-conventional family of lower socio-economic status in an urban environment.

Non-fiction graphic novels can be every-bit as compelling as its fiction. The graphic memoir, Hey Kiddo by Jarrett Krosoczoka is in my list because it is a powerful story dealing with themes of identity. With images rendered in a a soft limited pallet of oranges and browns, Hey Kiddo is Jarrett's account of growing up with his grandparents and coming to terms with his complex family situation - that is, having a mother who has abandoned him while she deals with her addiction to heroin, and having a father whom he has never met and whose name he doesn't even know. My reaction to this story surprised me. It had me in tears in several places. Despite having grown up in a household with two parents I could feel the pain of Jerrett's confusion and abandonment. Fassbender points out that "the desire to belong is not unique to a certain culture or generation." Krosczoka's images tell a powerful story. Futhermore, Hey Kiddo is also an effort toward increasing diversity in children's and YA literature which Short and others wish to see. It depicts a non-conventional family of lower socio-economic status in an urban environment.

~ Multimodal Responses to Literature Across the Curriculum

It is important for students of today to develop a variety of multiliteracies which go beyond listening, speaking, reading, and writing, to include viewing, creating, work with digital technologies, understanding and participating in the making of social and cultural cues, numbers skills, and the understanding of music and movement. All of these multiliteracies require student engagement with content and participation in the creation of meaning. I mentioned this earlier, but I will say again that I have been reflecting a lot on the idea that many students are "more interested in discussing meaning when it is related to a specific task than when it is the primary response to a piece of writing" (Delvecchio, 2019). This idea is central to the module on multimodal response. While I have been using multimodal responses for years, after taking this course and thinking more about multiliteracies, I am even more motivated to offer students opportunities for student centered tasks which require response to intriguing questions based on personal perspectives and the students' own interests in the material. While the term multiliteracies frequently brings to mind digital communication, the muliliteracies that students need to acquire include more than digital literacy and multimodal responses do not need to be digital responses.

Love that Book: Multimodal Response to Literature by Bridget Dalton and Dana L. Grisham tells us "there is a growing body of research demonstrating the positive effect of mulimedia on learning, including promising evidence that composing with different modes can engage students in content and develop their literary analysis skills (Grisham& Wolsy, 2006; Jocius, 2013; cited in Dalton & Grisham, 2013)

What is Literacy in the 21st Century by Zachary Nicol is a video which shows how the work of the 'New London Group' is still relevant today and informs much of the push toward BC's new curriculum and what others have coined "21st Century Learning." I appreciate Nicol's definition of 21st Century Literacy as "an interactive and engaging mindset used in both producing and consuming content" (Nicol, 2014). This video summarizes what literacy means today and how we might best achieve it. I love that this video is, itself, a multimodal response from a student.

~ Diversity of Text

Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Doors by Rudime Sims Bishop presents a powerful metaphor addressing the need for diverse literature. I love this metaphor - the mirror which represents when a reader is able to find something familiar or is able to see themselves represented in the text; the window which allows other readers to see the lives of those who are different from themselves; and the sliding glass door which may allow readers "to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author" (Bishop, 1990). Her metaphor has become an important framework for later academic discourse on this topic.

Mirrors and Windows: Teaching and Research Reflections on Canadian Aboriginal Children's Literature by Lynne Wiltse shares Ingrid Johnston's thought (2010) that "it is important to be able to recognize ourselves in a book, particularly if we, as readers, are from a culture that has been marginalized or previously unrecognized in literary texts in the west" (Johnston, 2019, cited in Wiltse, 2015). This article presents an important look at the problems of using predominately white Eurocentric literature in Canada when many of our students are Indigenous or from other cultures of the world. Wiltse hopes that "Aboriginal students in current and future classrooms will be on the winning side of hearing their own words and seeing their own faces in the texts they are given to read in our Canadian classrooms" (2015). I think this article is an essential read for any Canadian teacher.

The Secret Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali by Sabina Kahn is a book I finished reading this week and it is coming onto this list because how many books have you read about a LGBTQ Muslim teen? I thought so. It's my first one as well. The story, about a 17-year-old Bengali-American lesbian living in Seattle addresses the cultural in-betweenness of living an American lifestyle and having western friendships while also experiencing the conservative culture of her parents and their Bengali community. It also explores, in a nuanced way, the western presumption that queerness is white and the dangers of coming-out in a different cultural context. This story both reveals and dispels stereotypes. While the novel highlights the strong sexism and frequently brutal homophobia of Bengali culture, the protagonist herself is surprised to learn that not all members of her religious Bengali community will reject her because of her sexual orientation. Despite all the ways that this novel represents minorities, the theme of gaining independence while also maintaining sense of belonging is one that every reader can identify with. I really enjoyed the "sliding door" I was able to walk through to experience Bangali foods, customs, and family life both in America and Bangladesh.

The Secret Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali by Sabina Kahn is a book I finished reading this week and it is coming onto this list because how many books have you read about a LGBTQ Muslim teen? I thought so. It's my first one as well. The story, about a 17-year-old Bengali-American lesbian living in Seattle addresses the cultural in-betweenness of living an American lifestyle and having western friendships while also experiencing the conservative culture of her parents and their Bengali community. It also explores, in a nuanced way, the western presumption that queerness is white and the dangers of coming-out in a different cultural context. This story both reveals and dispels stereotypes. While the novel highlights the strong sexism and frequently brutal homophobia of Bengali culture, the protagonist herself is surprised to learn that not all members of her religious Bengali community will reject her because of her sexual orientation. Despite all the ways that this novel represents minorities, the theme of gaining independence while also maintaining sense of belonging is one that every reader can identify with. I really enjoyed the "sliding door" I was able to walk through to experience Bangali foods, customs, and family life both in America and Bangladesh.

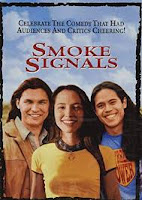

The film Smoke Signals and the literature this 1998 film is based

on are significant because they are complex stories that represent a

contemporary Native experience. They paint a picture of life on a Native

reserve and dispel the myth that Natives exist only in history. This

film was released in 1998 and is based on a collection of short

stories by Sherman Alexie entitled The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight

in Heaven. The film is largely based on one

particular story, "What it Means to Say Phoenix Arizona," but

pulls from other stories in the collection as well. These

variations of the same story offer a multi-modal experience.

The film Smoke Signals and the literature this 1998 film is based

on are significant because they are complex stories that represent a

contemporary Native experience. They paint a picture of life on a Native

reserve and dispel the myth that Natives exist only in history. This

film was released in 1998 and is based on a collection of short

stories by Sherman Alexie entitled The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight

in Heaven. The film is largely based on one

particular story, "What it Means to Say Phoenix Arizona," but

pulls from other stories in the collection as well. These

variations of the same story offer a multi-modal experience.

Fatty Legs and its sequel A Stranger at Home by Christy Jordan-Fenton and Margaret Pokiak-Fenton

are included in my curation because the imagery and the prose are beautiful (the prose if full of metaphors), and the story presents Inuvialutan culture. While Fatty Legs is about Oleman's experiences of residential school, the sequel shows what many residential school survivors experienced upon returning home. These non-fiction texts provide a mirror for Indigenous readers and can be used to teach history and such concepts as forced cultural assimilation. Fatty Legs is a text Wiltse talks positively about in her article, as it "offers a means for children and youth to explore historical perspectives" (Wiltse, 2015) and has the potential to "interrogate notions of a homogenous sense of nation" (Johnston et al, 2017; cited in Wiltse, 2015).

~ Children's Book Creators in the Classroom

This module articulates the value of hearing from authors and illustrators. Delvecchio mentions a study by David Ward which finds that "creator visits [...] empower children, giving [them] a sense that indeed they could do that" (Delvecchio, 2019). According to Delvecchio the inclusion of an author's voice provides another dimension for students to consider and "can [...] be considered a multimodal approach to children's literature" (Delvecchio, 2019). Hearing the thoughts of the creator can provide new insight and another layer of meaning to a work of art. One of my closest friends is a novelist by the name of Angie Abdou. Our twelve year old sons brought us together, but we became friends over our love of books and the library. I am so grateful for her in my life because she has brought not only herself, but many other authors into my library, my life, and my classroom. Because of her it is easier for my students and for me to imagine becoming a writer. Module 11 reminds me to be grateful for her and to continue to expose my students to the voices of writers.

Jarrett Krosoczka - How a Boy Became an Artist shows the power of educators to positively impact their students. It also shows that exposure to other artists helps students see themselves as artists. Having now read material by Krosoczka I was fascinated by this video.

Interview with Markus Zusak, author of The Book Thief . Zusak provides a beautiful account of what inspired him to write The Book Thief and a fascinating glimpse at his thought process and the development of the story's narrator - Death. I will show this interview if I teach this novel.

~ The truth about stories is, that's all we are - Thomas King

I would like to end the way I began - with this quote which comes from Thomas King's CBC Massey Lecture Series entitled, The Truth About Stories (now also published in book form). According to King, behind every action there is a story. Embedded within our stories are our values, hopes, dreams, and ideologies. It is the stories we have heard and the stories we tell ourselves which motivate our actions and our attitudes. This course makes me think of Thomas King's idea because through many of the articles and modules studied I am made aware of the power of stories for good and also for manipulation. I see how our ideologies are both captured in stories and also spread through stories. Stories are a tremendous gift and also a great responsibility. I'm grateful for the time that I have been given to think about their place in my classroom and my life.

I would like to end the way I began - with this quote which comes from Thomas King's CBC Massey Lecture Series entitled, The Truth About Stories (now also published in book form). According to King, behind every action there is a story. Embedded within our stories are our values, hopes, dreams, and ideologies. It is the stories we have heard and the stories we tell ourselves which motivate our actions and our attitudes. This course makes me think of Thomas King's idea because through many of the articles and modules studied I am made aware of the power of stories for good and also for manipulation. I see how our ideologies are both captured in stories and also spread through stories. Stories are a tremendous gift and also a great responsibility. I'm grateful for the time that I have been given to think about their place in my classroom and my life.

Dalton, B., & Grisham, D. L. (2013). Love that book: Multimodal response to literature.The Reading Teacher,67(3), 220-225.

In this module I reflected on the contradictory idea that books both shape our perceptions of childhood and are shaped by society's perception of childhood. I am fascinated by the idea that stories are the result of books written by an adult for the child and that the child in the book is the image of the type of child the author has in mind - a combination of the views they have inherited from their society and of their own remembered experiences of childhood. It is important to understand these concepts in order to understand the degree to which our own society and past experiences as a child have shaped our book preferences and the books we share with children.

The video, Maurice Sendac on Being a Kid helped me to think about the degree to which our childhood experiences shape our view of childhood. Maurice's childhood was less than idyllic, as many childhoods are. He faced difficulties but was able to persevere through them. He was exposed to and appreciated European stories about children in terrifying situations. These experiences shaped his perception that childhood is a tough time, but children are capable of solving complex problems and capable of surviving adverse circumstances. These views, in turn, have shaped his writing, which is never condescending and does not downplay the struggles children face. Sendak says, "I still think the same way I did as a kid. I still worry. I'm still frightened...Nothing changes." I clearly when I was a child I disliked when adults talked down to me. I remember when I was six years of age reflecting on the fact that I felt myself a fully capable intelligent human being with complex thoughts, but that most adults did not realize how capable and intelligent I actually was. Sendak's understanding that much of what we think and feel does not change between childhood and adulthood gives his work a depth and complexity that some children's stories lack.

Historian's Discovery of Childhood by W. Frihoff was a dense, but fascinating read exploring the way societies have viewed childhood over time. I was interested to learn that the entire concept of childhood is quite recent to Western thought. I was especially intrigued by Frigjoff's suggestion that children and YA literature is always written by an adult to an idealized child. When writing children's books adults have the child they once were in their minds, therefore creating texts about imagined children of a prior time and place. An extension of this idea is echoed in the articles by Hill, Rata, and Short. These later articles postulate that this situation of the adult writing for an imagined child creates an imbalance of power between a text and its young reader. Rata writes "T]hese books must represent the adults' values, morals, knowledge, ideas that are manipulating the child reader" (Rata, 2014). I will discuss Rata's article later in this curation, but I wanted to point out how she has gone further with Frihoff's initial premise in suggesting children's texts may have tremendous ideological influence over the reader.

Lucy Maud Montgomery's Anne of Green Gables is included in my curation because it is an example, for me, of a story from my childhood which had an influence on my values and interests. It helped to shape my love of nature, a belief in the independence of women, a value for creativity and individual expression, a sense of community mindedness, and an interest in reading, writing, and teaching. Perhaps we are more susceptible to the texts of our youth because it is a time of rapid intellectual, social, emotional and physical development. Our identities are more malleable. Irina Rata writes, "Children's books have the potential to be the most influential books in someone's life, being the first books that a person reads; having the power to form the reader's personality, character, value system, and even the reader's taste" (Rata, 2014).

~ Context and Literary Canon

This module in combination with the last one helped me to see how my society and my past experiences as a child have influenced my personal canon. I recognize that my book selections for young children are a result of my own time period and culture. They have shaped my perceptions of childhood as a time for imaginative play, learning, and for finding a place in the world with others. These perceptions have their root in an idea of the child has both "socially constructed" and as a "psychologically and intellectually developing human" (Delvechhio, 2019). Also, the reflection task I completed - to create a canon for the first ten years of a child's life - also lead me to see the degree to which my book selections are a product of my own white privilege as they do not represent my racial or ethnic diversity. A next step for me will be to keep this awareness going forward so that my selections become more inclusive of a diverse range of cultures, genders, abilities, and socio-economic perspectives.

Critiquing and Constructing Canons in Middle Grade English Language Arts Classrooms by Amanda Haertling Thein and Richard Beach had me thinking about the importance of becoming aware of all the forces of canonization and also the potential to invite students to become active participants in critiquing and constructing it. The article states, "This collaborative approach to critique and construction has the potential to empower rather than limit students as they select and engage with literary texts" (Thein and Beach, 2013).

Reconstructing the Canon by Devon Black (an article I found through research) describes the current university canon as predominately written by "white, heterosexual, dead males." I do not completely agree that the canon of my own university studies consisted primarily of "white, heterosexual, dead males." When I thought back to my own experiences I recall reading a fair number of texts written by women, but the texts were often written by authors who were "white and "heterosexual." I appreciate that the article lead me to reflect on my own university studies. I also like that the article supports an approach which does not abandon the classics, but rather adds to them: "balancing inclusion of diversity in literature and an ongoing focus on the tradition canon is just that: an "and" not an "or"....English teachers [...] should teach students to love reading and should provide them with the ability to understand experiences beyond their own"(Black, 2018). What I haven't yet been able to sort out is how to find enough class time to incorporate the classics alongside more diverse texts.

Literacy Leadership Brief. Expanding the Canon: How Diverse Literature Can Transform Literacy Learning by The International Literacy Association (my own research) advocates for the redefining of what makes a classic as "a title that succeeds to an unusual degree in expressing the shared experiences of humanity through an artistically significant creation" and suggests a "more expansive approach to literature selection that can redesign and ultimately redefine the narratives that define the classroom library" (The International Literacy Association, 2018). I agree with the idea of finding diverse pieces of literature that still exemplify great writing. I also appreciated the article's suggestion that if students are regularly exposed to diverse texts they will "internalize issues of diversity as part of the human condition, not as adjunct material for certain holidays or topics" (International Literary Association, 2018).

~ Poetics: What Makes Some Literature Literary

This is one of my favorite modules to read and think about because in some ways it has been a part of my life's work. From the time I was a teenager I have been thinking about great books and great passages of text. When I was in grade nine I began keeping a journal with passages that I admired or that inspired me. I was inspired by the idea that children's literature is often great writing.

Module 5: Poetics: What makes Some Literature Literary by UBC Professor Jennifer Delvecchio defines writing which is literary as that which provides new perspective, contains multiple layers of meaning with themes, and uses language uniquely. These module notes were a good starting point which laid a foundation for further reflection and reading about "literary" texts.

Children's Literature - A Cinderella Story by Irene Rata points out that much children and YA literature, "may surprise the reader with unexpected depth and intricate narrative, beautiful language and deep subtle human motives, literary innovations, and difficult themes treated with grace" (Rata, 20). The article argues that definitions of children's and YA literature are inconsistent and that it has been largely dismissed or ignored by literary critics. The article points to a number of qualities that make it unique and deserving of literary study. I particularly appreciated Rata's point that "as a genre [children's literature] mirror's the literature in general with all its genres and forms" and that it is "an interesting object of study, where one may rediscover the pleasure of reading, and uncover unknown things" (Rata, 2014).

The Book Thief by

Markus Zusak, is included in this curation because it is a fine

example of a story which fits Rata's description of great YA

writing. The plot is far from simple, containing a non-linear

narrative with multiple plots and sub-plots, multiple secondary characters, and

multiple points of view. It also employs anachronies - flashbacks

and flash-forwards, prolepsis - the anticipation of possible objections in

rhetorical speech, and analepsis - a past event narrate later.

These are all mentioned in Rate's article as frequent features of adult

literature, but also a surprisingly large amount of children's and YA

literature. I also loved this novel because, above all else, it was a

story about the power of words.

The Book Thief by

Markus Zusak, is included in this curation because it is a fine

example of a story which fits Rata's description of great YA

writing. The plot is far from simple, containing a non-linear

narrative with multiple plots and sub-plots, multiple secondary characters, and

multiple points of view. It also employs anachronies - flashbacks

and flash-forwards, prolepsis - the anticipation of possible objections in

rhetorical speech, and analepsis - a past event narrate later.

These are all mentioned in Rate's article as frequent features of adult

literature, but also a surprisingly large amount of children's and YA

literature. I also loved this novel because, above all else, it was a

story about the power of words. Empathy: Narrative Empathy and Children's Literature by K. Mallan is an article which is sticking with me because it argues against what I have, for years, believed to be true. The article refutes the nation that reading has an impact on the ability of the reader to "become more empathetic, tolerant, and better people" (Mallan, 2013). This article made me uncomfortable, but I appreciated its nuanced and challenging discussion of the way empathy works in stories and the notion that "fiction that engages a reader with the emotional plight of a character does not necessarily translate into actions in the real world towards people who are similarly suffering, marginalized or victimized" (Mallan, 2014). There was a lot to unpack in this article. Mallan also points to oversimplification in reducing complex situations to binaries such as "victim" and "savior" and criticizes "one off acts of empathy while failing to address institutional, corporate, systemic abuses of power that are much more toxic, powerful, and oppressive than anything an individual can individually commit or, conversely, repair" (Mallan, 2014). If I am to accept what this article is saying then I agree with the article's conclusion that urgent work of pedagogy and children's literature studies in needed to realize the potential [critics such as Rorty and Nussbaum see] of literature for reimagining a more empathic, moral, and compassionate world" (Mallan, 2014).

Literary Fiction Readers Understand Other's Emotions Better,

Study Finds by

Alison Flood reports on findings that "literary fiction

... helps improve readers' understanding of other people's emotions...."

(Flood, 2016). The study notes the improvement does not happen with what

Flood calls genre writing and postulates that "the implied (rather than

explicit) socio-cognitive complexity, or roundness of characters, in literary

fiction prompts readers to make, adjust, and consider multiple interpretations

of characters' mental states" (Study in Flood, 2016). I found it

interesting that this study shows an improved ability to read the emotions of

others, but the article does not claim that this improved ability leads to

greater empathy.

The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time by UK writer Mark Haddon, is in

my curation because it presents round characters, such as the autistic

protagonist and his mother. Instead of presenting an image of maternal

gentleness and protection Christopher's mother is depicted as a person

with complex and competing motivations and emotions. The complexity of the

motherly depiction defies stereotypes. The text neither idealizes her or

turns her into a villain. Using Rudine Sims Bishop's metaphor

(which I will discuss later), the text is one which offers a mirror to readers

who process the world differently (such as people with autism) and to those who

have experienced family dysfunction. The text is a sliding glass

door to other readers, "allowing them to walk through in imagination to

become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author"

(Bishop, 2018; cited in Delvecchio, 2019). The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time may help readers to do what Christopher cannot

do - that is, infer the feelings of others.

The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time by UK writer Mark Haddon, is in

my curation because it presents round characters, such as the autistic

protagonist and his mother. Instead of presenting an image of maternal

gentleness and protection Christopher's mother is depicted as a person

with complex and competing motivations and emotions. The complexity of the

motherly depiction defies stereotypes. The text neither idealizes her or

turns her into a villain. Using Rudine Sims Bishop's metaphor

(which I will discuss later), the text is one which offers a mirror to readers

who process the world differently (such as people with autism) and to those who

have experienced family dysfunction. The text is a sliding glass

door to other readers, "allowing them to walk through in imagination to

become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author"

(Bishop, 2018; cited in Delvecchio, 2019). The Curious Incident of the

Dog in the Night-time may help readers to do what Christopher cannot

do - that is, infer the feelings of others.~ Sequential Visual Narrative Forms

This module was a study on the role of images in not only picture books, but also comic strips and graphic novels. As someone who loves art, I have a deep appreciation for images, but I have had only a little experience reading comics and even less experience with graphic novels. For that reason the last few weeks have been a delightful immersion into this form and have opened my eyes to their value for instruction and as literature. Images, like text, can do the work of telling a story using all the same genres of other novels and with all of the possibilities of being of literary merit. Plot, character, events, and actions may be conveyed through the language of images rather than words. I am discovering the potential of the medium to tell a story, convey complex ideas across subject areas, use with students as a type of multi-modal response, and move me to a sense of wonder.

A Meditation on the Good Old Picture Book by Janine Forbes-Rolfe points out the literary qualities of a picture book. The article explains, "The humble picture book may seem deceptively simple in form, but the best books always manage to belie this apparent simplicity, creating rich experiences that potently shape how young learner makes sense of the universe. I appreciated this article's perspective that a picture book can be literary and that the best picture books are foundational to how young minds begin the early process of constructing meaning and defining their surrounding" (Forbes-Rolfe, 2015).

Are You My Mother by P.D. Eastman is the type of foundational book Forbes-Rolfe says a picture

book can be. Written in 1960, this picture book story is about a baby bird in

search of his mother. He tumbles to the ground after hatching while his

mother is away from the nest. What ensues is an endearingly sweet and

funny quest to find his mother. The effectiveness of this story

rests not only on the humorous illustrations and dialog - the repeating

question "Are you my mother?" and "You're not my mother,"

but at the metaphorical level of the reader seeing his or her own search for

identity and belonging in the baby bird's search. The story

meets definitions of what is literary as presented by Delvecchio in Module

5 in that it provides new perspective, contains multiple layers of meaning

with themes, and uses language uniquely (Delvecchio,2019).

The

illustrations in Are You My Mother are essential to the story,

as without them the reader would not understand who or what the little bird is

talking to and would not understand how the baby bird is reunited with its

mother. These illustrations are rendered with a limited color palette

of muted brown, yellow and red. The images focus solely on the baby

bird and his search, without any other details. Despite it's brevity, simple images,

and simple sentence structures, it manages to touch on the universal theme of

belonging.

Are You My Mother by P.D. Eastman is the type of foundational book Forbes-Rolfe says a picture

book can be. Written in 1960, this picture book story is about a baby bird in

search of his mother. He tumbles to the ground after hatching while his

mother is away from the nest. What ensues is an endearingly sweet and

funny quest to find his mother. The effectiveness of this story

rests not only on the humorous illustrations and dialog - the repeating

question "Are you my mother?" and "You're not my mother,"

but at the metaphorical level of the reader seeing his or her own search for

identity and belonging in the baby bird's search. The story

meets definitions of what is literary as presented by Delvecchio in Module

5 in that it provides new perspective, contains multiple layers of meaning

with themes, and uses language uniquely (Delvecchio,2019).

The

illustrations in Are You My Mother are essential to the story,

as without them the reader would not understand who or what the little bird is

talking to and would not understand how the baby bird is reunited with its

mother. These illustrations are rendered with a limited color palette

of muted brown, yellow and red. The images focus solely on the baby

bird and his search, without any other details. Despite it's brevity, simple images,

and simple sentence structures, it manages to touch on the universal theme of

belonging.  The Day the Babies Crawled Away, by

Peggy Rathmann also meets definitions of writing which is

literary and has become important in my thoughts about children's

literature over the past several weeks as it was the starting point for my

curation in Assignment 2. Similar to Are You My Mother, this

story also contains images which help to narrate the story. The pictures